In my first week-long solitary meditation retreat, in an isolated cabin overlooking the Gulf of St. Lawrence, I came face to face with my own mind — and several hundred other wild things. What follows are some reflections on getting to know the creatures I found inhabiting my retreat cabin — and my mind — and what I learned from them. This is Part Two of a two-part series. Click here to read Part One.Day 5The weather has turned wild and wrathful. The wind is now blowing down from the highlands so hard that it’s pushing the waves

out to sea, and not letting them break on the shore. Typical Cape Breton springtime weather.

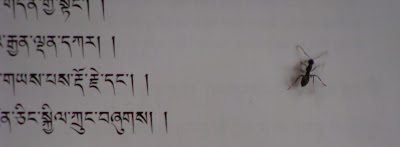

I have a “retreat protector” — a friend who is supporting me in my retreat by bringing me food each day. This is a great blessing, since I get much better food than what I would cook for myself, and I don’t have to spend as much time preparing it — which leaves more time to focus on the retreat itself. Today at lunch I received a special surprise: cake and ice cream, from the farewell party for one of the temporary monks who is leaving now that his one-year commitment is up. While I was devouring the ice cream, my eyes were once again drawn to the floor by one of the ants. This one appeared to be sick or injured, and it was dragging itself around on its side, with great struggle and effort — going in circles, and trying to stand up straight, and collapsing onto its side again. My ice cream and cake didn’t taste quite as good when I was watching a sentient being — however small it might be — struggling in the throes of death right in front of me.

Still, when I dig deep inside myself, I cannot say that I feel the same degree of empathy for these ants that I would feel for another, larger creature in the same circumstances. If it was a dog or a cat convulsing in its final moments in front of me, I could not sit here eating my ice cream at all — I would be in tears, trying to do something to comfort the creature and ease its suffering. But the ant's agony does not even rise to the occasion of halting my ice cream consumption. And there is nothing I can do to comfort an ant — I cannot pet it or soothe its fears or make it more comfortable. I can only watch, and offer as much empathy and good wishes as a human being can possibly extend to an ant.

And what about this macabre charnel ground business of theirs? If there were a bunch of wild dogs passing back and forth through this cabin while I was meditating, dragging behind them canine corpses and carrying in their mouths the severed, bloody heads and legs and abdomens of other dogs, I would be upset, to say the least. But that is precisely what is happening with these ants, day and night, on a miniature scale — and it only arouses my curiosity and attention, and a glimmer of compassion that is, by comparison, shallow and superficial. I wonder why. Is it because they are so tiny? Because there are trillions of them? Because their form, and their way of life, is so alien and bizarre to us that we cannot imagine they suffer as we do? Do we suppose they have no feelings, no consciousness, no will to continue living?

That is, I guess, the view held by many people, who would have no qualms about stepping on any ant that got in their way or had the audacity to make an appearance in their kitchen. We now have industrial factories that produce nothing but toxins to kill ants, and people whose sole profession is to exterminate them. The popular consensus seems to be that their very existence is an affront to the human race, and they must be annihilated to make us more comfortable.

Day 6The wild and wrathful wind has been blowing for two days, and has grown even stronger. I am uneasy about the many swaying trees around the cabin. They are brittle spruce trees with shallow roots, and many are already dead from a raging Asian spruce beetle infestation that’s wiping out whole sections of the forests on Cape Breton, and throughout Canada. They snap like matchsticks in these winds, and the woods are littered with fallen trees — as this cabin is littered with fallen ants.

My meditation practice started out in a thick fog this morning, with a wild wind of discursiveness blowing in my mind. But by the end of the day, the fog and clouds in my mind have cleared, and the discursive wind has stopped blowing; I feel remarkably peaceful. Curiously, the same thing has happened with the weather outside. In my last meditation session of the day, I feel inspired to do an extra rosary of my practice, and while I am at it the sky outside clears and the wind stops blowing. The sea becomes still and the air itself is now gentle and warm and soft like a baby’s blanket — a perfect springtime evening. The sun sets on the calm ocean with ridiculous splendor and majesty. It is as if a dreary black-and-white film noir has suddenly turned into a lush Bollywood musical in vivid technicolor. The winter here — which lasts, I have realized, about six months — has been so relentlessly gray and cloudy that I have almost forgotten how breathtakingly beautiful and saturated with color this place can be in spring and summer. Tonight it looks and feels like a picture postcard that I want to send to all my friends, with the inscription: “Wish you were here.”

It is April Fool’s Day, and I came to the Abbey one year ago today.

Day 7The gray fog and mist are back, and the sea and sky have merged into one again. But there is no wind, and the water a hundred feet below — what I can see of it, anyway — is eerily calm.

Last night as I was going to bed I witnessed a murder — or at least, I think that’s what it was. One of the little worker ants had one of the big winged ants and was dragging it off by its antennae. But this one was no corpse; it was very much alive, and was trying to resist being dragged away to wherever the smaller ant was taking it. But, drunk or stoned on whatever it is that makes these winged ants so slow and dull and ineffectual, it was powerless against the smaller ant despite its much larger size. Perhaps the winged ants have no pincers to defend themselves; if they did, this one could have snapped the worker ant in two pieces quite easily. His six legs struggled against the pull of the smaller ant, but his strength was no match for it and he was being dragged away kicking and screaming — or he would have been, if ants could scream. I found the whole scene quite disturbing; but I decided I did not want to know how it would end, and I turned off the light and went to bed. This sinister turn of events has severely rattled my theory that these various kinds of ants are all getting along together peacefully. Apparently, it is not only the dead ones who can get dragged away and “disappear.” I had better watch my back in this place.

Over breakfast this morning I recalled an old scary movie called “Them,” in which America is invaded by giant, man-eating ants. (It reminds me of what’s happening these days, with America being invaded by Sarah Palin and the Tea Party.) I remember being disappointed to learn that the terrible monsters — so fearsome and indescribable that they could only be known as “Them” — were nothing more than oversized ants. I was expecting, I don’t know, nameless and shapeless creatures from outer space, or something like that. Giant, man-eating ants just seemed so…plebeian.

And yet...now that I am getting up-close and personal with these ants, I am thinking how scary it would actually be if the size differential between us were reduced — or even, unthinkably, reversed. Imagine looking up at those black, unemotional eyes staring back at you, having those sharp and unrelenting pincers closing around your neck, and being dragged away to their lair and chopped up to become food for the ant kingdom.

“The ant kingdom.” It’s a dumb phrase. Ants don’t have kings, they only have queens. But “the ant queendom” doesn’t sound quite right. Anyway, it’s strange, too, to call their central figure a queen. She is the only one in the colony who can lay eggs, and that is the only thing she does. She does not resolve disputes or issue royal decrees, and she probably has little idea of what's going on in the world outside her colony. Trapped in her chamber, which she can never leave, bloated fat with eggs, all day long she does nothing but pump out egg after egg after egg. Other ants — nurses and midwives — are waiting nearby, and quickly move in to lick each egg case clean and coat it with saliva that contains mold-inhibiting chemicals. If the eggs begin to grow mold, as everything rapidly does underground, they will never hatch. The queen’s innermost, regal chamber is a nursery, and Her Majesty is really an egg-laying machine, a slave to her own reproductive role.

A friend who lives nearby has another small cabin attached to her property, and recently had an invasion of carpenter ants. They had to be dealt with decisively to protect the cabin from being eaten as the ants’ dinner. This was greatly distressing to my friend who is a very ethical Buddhist and wouldn’t dream of intentionally harming even the smallest creature. But “carpenter ants” is another misnomer. Carpenters build things — but carpenter ants only destroy them. I suppose they’re called that because they’re skilled at working with wood. And they leave scrap wood and piles of sawdust everywhere, which is the other thing carpenters are known for.

Day 8Last night I had insomnia. I unplugged the nightlight and opened all the blinds next to my bed and watched the stars. I’m from New York City, where maybe on the best night of the year you can see five stars, and even those are probably planets or satellites. Here you can’t fathom the number of stars in the sky, the number of other solar systems and worlds that exist out there. The Big Dipper was hanging right above my bed, pouring down on my head whatever it has been dipping and pouring all these billions of years. Through the walls and the floor of the cabin, if I listened closely, I could hear a strange, rhythmic sawing noise, a vibration that sounded curiously like muffled voices coming from someone’s television in the next apartment. I am convinced it was the sound of that fat weasel beneath the cabin, snoring.

Eight days a week. Today is pack-up-and-move-out day. It’s time for me to go back and rejoin the community at the Abbey. My first solitary retreat is over. But to be truthful, it was never really very solitary. There were no other people here, but I was certainly never alone. Living for a week among these ants and flies and squirrels and weasels, I was simply part of a different community in Cliffhanger cabin, a community that will continue here after I am gone. These creatures welcomed me in their own way, and seemed to have no problem with my presence. With all these ants crawling everywhere, including up my pants, not one of them ever bit me in these seven days. So I have felt at home in this community of solitude, and I hope I have not been an obnoxious guest. Perhaps I will see some of these same faces again on my next retreat.

But some of them I would prefer not to see again. Like the spider crawling next to my breakfast table this morning. Most of the spiders around here are harmless wood spiders, but this one was something else altogether. Its body was fat and bulbous and dark, with a sinister purple tinge. People around here often say to me that there are no poisonous spiders native to Cape Breton. I say those people are full of hogwash. I have seen brown widows here, which are the little-known cousins of black widows; they are not

quite as poisonous but they're no kittens, either. Maybe poisonous spiders are

not native to these parts, but then neither is anyone else living at the Abbey. We’re all recent immigrants here.

No normal person can look at a spider like the one at my breakfast table this morning without getting the heebie-jeebies. Maybe it isn’t going to kill you, but it’s going to leave a permanent mark. I’m glad I didn’t see him until the morning of my departure; I would have been thinking about him the whole week, looking around anxiously during my meditation sessions, imagining him crawling onto my cushion or into my bed. But I suppose every community has its members who push your buttons, whose presence you find difficult to tolerate, the ones whose faces you’d prefer never to see again. That’s life in a community. You either suffer from it, or you learn to be more tolerant and to let go of personal preferences.

This morning as I was coming back into the cabin after carrying some of my things over to the Abbey, I was greeted at the door by one of those dim-witted winged ants, which crawled towards me slowly in its clumsy way, like an eager puppy. I felt a strange surge of tenderness for it, and even affection.

I was happy to see it. But is that really possible? Can a human being think of an ant fondly, like a cherished pet? Maybe I could pack up some of these ants and take them back to the Abbey with me, and keep them in an ant farm. We’re not allowed to keep cats or dogs at the Abbey, and I really do miss having pets to care for.

On second thought, no. I think the test of whether or not a creature would make a good pet is if I would want it sleeping in the same bed with me. I’m sorry to say that these ants — and spiders, and flies, and squirrels, and weasels — definitely don’t pass that test. Wild things, I

think I love you — but do me a favor, and stay out of my bed. I don’t love you like that.