Tragedy struck in 1922, shortly after my grandfather's family had migrated by wagon train from Texas to Oklahoma. The seven family members who died that one horrific month, exactly a century ago, are buried together in a small cemetery in a rural town near where my mother grew up.

As many as 10 family members came down with typhoid fever, including my grandfather who was just a boy at the time. The survivors recalled desperately "turning from one sick bed to another" as they tried to comfort and care for those who were ill.

The person who looms largest in my mind here is my great-grandmother, Mary. The seven people who died that month were all her children and grandchildren.

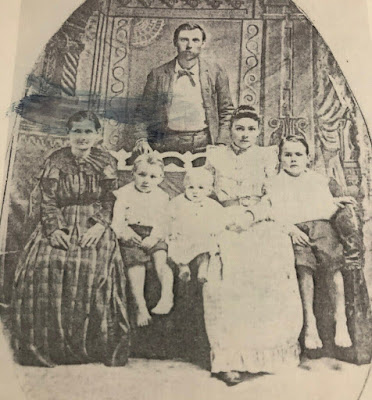

|

| My great-grandmother Mary, in the white dress, circa 1912. My grandfather was not yet born when this photo was taken. |

I try to imagine myself in her shoes. I try to fathom the cataclysmic loss she suffered in such a short period of time. The sheer scale of it makes the mind reel.

I wonder how she survived. I don't mean surviving typhoid — I mean how did she go on living after such a personal apocalypse? How did she not die of grief? How did she not lose her mind?

I asked my aunt Nova, the family historian, how she thought her grandmother managed to go on.

"She didn't have any choice," Nova replied. "She had all those other kids and grandkids to look after."

"I can't go on. I'll go on," the existentialist Samuel Beckett wrote in his novel The Unnamable. So that's it. You go on because it's choiceless. Death will have its way with you, but so will life. You rise from the ashes, pick up the nearest spoon, and use it to put food in the mouth of the next hungry child, sister, husband, friend.

I exist today because typhoid failed to kill my grandfather, and because of my great-grandmother's resilience. A full century later, hundreds of people in my extended family exist for the same reasons. Babies are still being born today on this family tree. We are the living, and the ones who are yet to live.

For the rest of her days, Mary never went back to the cemetery where her seven children and grandchildren were buried. I don't fault her for that. She didn't want to forget about the loved ones she had lost. But I suspect that the wounds in her soul were so deep — unfathomable even for her — that to risk reopening them would have been too much to bear. Others around her, including my grandfather, needed her to go on, and that was the only way she could.

No comments:

Post a Comment